Doug McKelvey chooses his words carefully.

This is true in more ways than one. In fact, thoughtfulness is a good way to surmise McKelvey’s posture; if you’ve spent more than 30 seconds with one of his liturgies in his 2017-release Every Moment Holy, you know this to be true. Every phrase and punctuation mark feels intentional, as if molded on a potter’s wheel.

A copy of Every Moment Holy.

Covering topics like stargazing, paying bills, moving into a new home, and morning coffee, McKelvey’s liturgies bring a spiritual weightiness to the oft-overlooked areas of everyday life. They illuminate inter-connectedness between heaven and earth in a newfound way.

He’s part poet, part theologian, part everyman.

But to know Doug McKelvey is to know this isn’t just a fanciful project he happened into.

Rather, this is part of who he is. Liturgy isn’t just a trend he’s caught up in so much as a discipline that’s shaped his own heart in understanding the transcendent realm.

As someone who grew up in the church in a decidedly non-liturgical tradition, McKelvey is a peculiar choice to lead the charge for liturgy-enthusiasts. In fact, it was through a friend’s invitation to attend an episcopal church service where he was first introduced to liturgy through the Book of Common Prayer.

Then, things changed.

“Something resonated,” McKelvey said in a December 2019 interview with the Center for Faith + Work Los Angeles. “The truth in it was expressed in a way I could trust.”

For many, this notion of trustworthiness in the lineage and care given to a liturgy has rung true.

A sketch of Doug McKelvey.

It’s not that these truths and distillations of theological complexity are watered down, but rather they’re carefully repackaged without losing their essence in an effort to help them catch afresh in the lives of readers and hearers. It’s a labor of love, and that’s partly how you know it can be trusted and must be held with a degree of seriousness.

It’s the layered notion of artistry that captured him and captures him still. It’s what keeps him coming back to the well, entering into the creative process, to help recapture a bit of the wonder.

“We owe something—our love and worship—to our creator,” McKelvey said. “Liturgy is effective insomuch as it is one of the things that fits into that ongoing process and pattern in our lives of being conformed to the image of Christ, sanctified, and dying to ourselves.”

The Road to Writing

To understand McKelvey you must first consider that he’s always been a writer. It’s in his blood.

After growing up in East Texas, McKelvey moved to Nashville in 1991, before the glitz and glam of the “It City” had taken over, at the request of Charlie Peacock (Grammy-winning producer of Joy Williams, Ben Rector, The Lone Bellow, and The Civil Wars) to participate in the early beginnings of the Art House Foundation.

“We owe something—our love and worship—to our creator. Liturgy is effective insomuch as it is one of the things that fits into that ongoing process and pattern in our lives of being conformed to the image of Christ, sanctified, and dying to ourselves.”

Peacock saw things McKelvey had written and asked if he wanted to try a song co-writing experiment.

To McKelvey’s delight, “I immediately said ‘Of course!’” But then a yearlong wait ensued before he mentioned it again and the experimentation took place. Once it finally did, the first few songs were “almost immediately” cut on a project Peacock was producing. For McKelvey the patience and experimentation paid off as he penned more than 350 lyrics recorded by a handful of Nashville staples including Switchfoot, Kenny Rogers, Sanctus Real, and Jason Gray in his songwriting career.

But the impending MP3 bubble burst left McKelvey in a tight spot after seemingly finding a vocational home.

“As someone who had one income stream—I wasn’t a producer, wasn’t an artist—I was only making 25 percent of what I had been,” McKelvey recalled. “I had three young kids and was trying to pay bills, so I sort of saw the writing on the wall, figured out pretty early on, and adjusted mentally to think that the industry wasn’t going to get ahead of this.”

After taking a few film courses in Los Angeles and getting into the video realm, McKelvey’s next steps felt a bit blurry. He was at a crossroads. Making ends meet took precedent and his vocational call as a writer began to fall by the wayside. He still wrote, it was just no longer for a paycheck.

His vocational journey even pivoted to work as a sexton—”an old name for a facilities manager,” he told me—and a Lyft and Uber driver as he attempted to find his next steps.

“I started thinking about how I wanted to spend the back half of my life,” McKelvey said. “But I always came back to writing books.”

A Lesson in Liturgy

To understand McKelvey is also to understand his depth.

In all the art he consumes, from movies to music to television, he appreciates works that are multi-layered in their expression. He wants not just thoughtful cinematography, but a well-conceived plot, and convincing actors. In an age of quantity, McKelvey seeks out quality in his artistic consumption. Likewise, this same drive shapes his own artistic work.

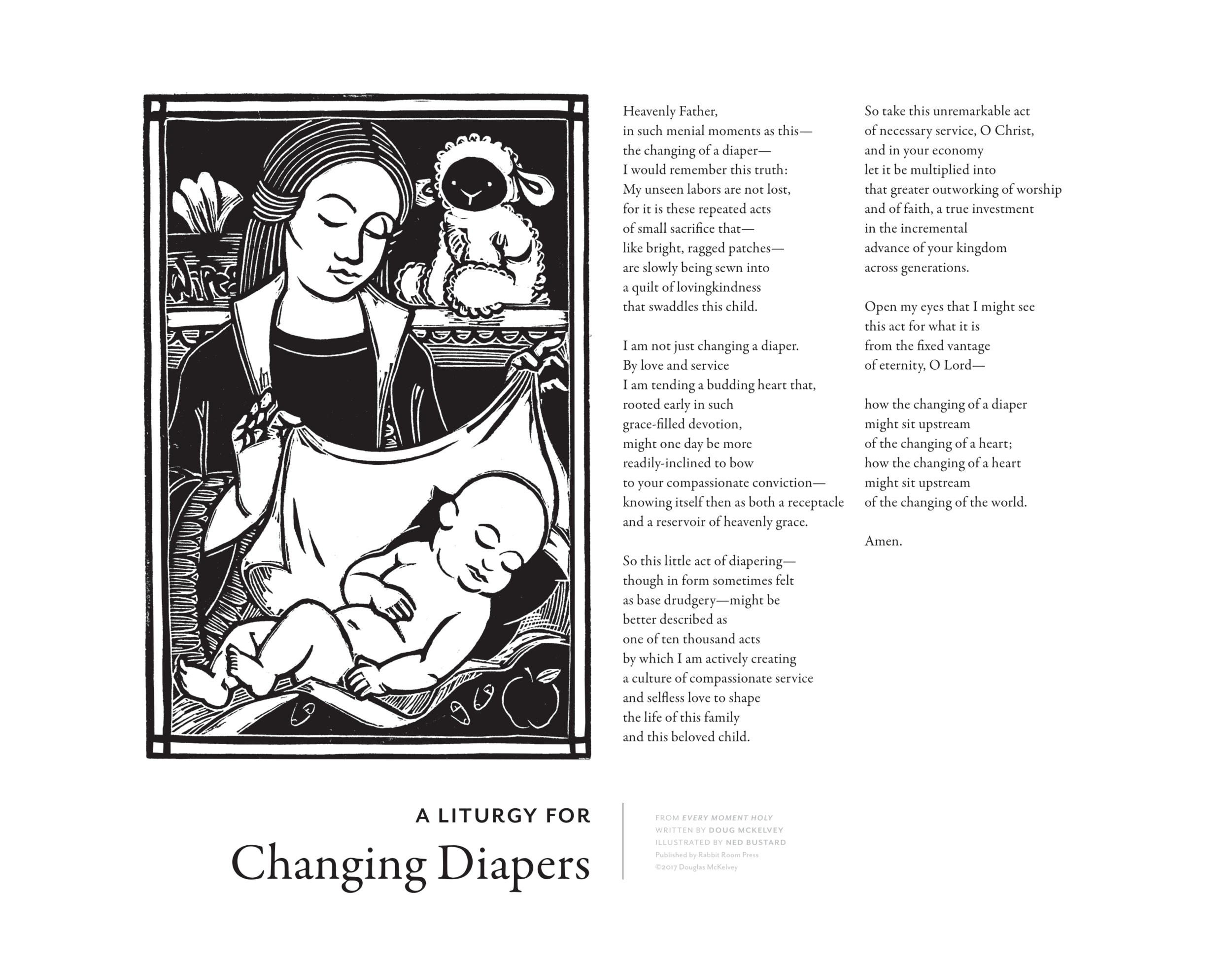

A print of a liturgy from Every Moment Holy, titled “A Liturgy for Changing Diapers.”

That’s one of the reasons he’s drawn to liturgies.

“They can be a distillation of truth such that they become formational to our thinking,” McKelvey offered confidently. “But part of how that plays out is the reshaping of our lives and how they become integrated into the rhythms of our lives.”

Liturgies themselves are part poem, part prayer, and part spoken word. In the same vein as prayers from the Book of Common Prayer, they are intended to pack a punch with strategically placed words that hit the reader or listener in the gut and leave them processing anew a long-held truth.

“If we’re willing to surrender ourselves and submit to truths God revealed, the very structure of our brain is changed over time. I think that liturgies can be a powerful part of that process.”

It’s not scripture, but the liturgies themselves drip with hope the gospel affords.

“If we’re willing to surrender ourselves and submit to truths God revealed, the very structure of our brain is changed over time,” McKelvey said. “I think that liturgies can be a powerful part of that process.”

This holds even for considering one’s vocation. In the daily work we engage, there can be much that feels rote and routine. Even mundane. But liturgies speak to just that. They help to reimagine what’s often overlooked. They bring the grayscale hue of our lives into technicolor.

Take, for instance, McKelvey’s liturgy for Changing Diapers.

“Heavenly Father,” the liturgy reads, “in such menial moments as this—the changing of a diaper—I would remember this truth: My unseen labors are not lost, for it is these repeated acts of small sacrifice that—like bright, ragged patches—are slowly being sewn into a quilt of lovingkindness that swaddles this child.”

McKelvey pondered the ways in which this necessary and often unpleasant task might intersect with the kingdom of God.

“Because the story told in scripture is God’s revelation,” McKelvey added, “it logically follows that every aspect of our lives is a part of what it means to live as followers of Jesus in this world at the time we’re given.”

This changes the way we work. By meditating, reflecting, and revisiting prayers like this, we are shaped and reshaped to see, in a deeper way, how our vocational lives are grafted into God’s unfolding story for a time such as this.

Rabbits, Bees, and Liturgies

It’s fair to wonder if beekeeping might have made McKelvey’s Every Moment Holy a reality. But before speculation gets the best of us, we need to outline another important piece of McKelvey’s story.

See, to know Doug McKelvey is to also know his fond appreciation for the Rabbit Room.

A community built around “a shared love of a certain sort of redemptive storytelling expressed in a variety of ways: fiction, poetry, film, songs, visual arts, etc.” McKelvey made a point that while some of those involved with the Rabbit Room are engaged vocationally as storytellers, many are not. The bond of the group centers around this notion that all human beings, made in the image of God, bear “echoes of the divine creativity” of their creator in the ways they engage their own daily work, explicitly in the arts or not.

It’s a home for those seeking to testify to the good, true, and beautiful through their artistic endeavors, and it’s a natural home for McKelvey, a self-titled author, poet, and oddity on the Rabbit Room website.

Started by Andrew and Pete Peterson in 2007, the Rabbit Room features events (namely The Local Show), their annual Hutchmoot conference (which is key to the conception of Every Moment Holy), and a publishing arm, the Rabbit Room Press.

After plugging away at a few short stories and books throughout his career, no explicit breakthrough had come to pass in McKelvey’s writing sans songwriting and film work. But Hutchmoot and the Rabbit Room community changed that.

Every year the conference has a special closing ceremony. Anyone who has attended a Hutchmoot can attest to this. But in 2015 Pete Peterson decided to do a variation that emphasized liturgy, where each attendee grabbed a piece of paper on their way into the final session, with special parts to be read aloud corporately. Titled “The Liturgy of Lost Rhyme,” the time consisted of an adapted text an as-yet-unpublished, genre-defying book McKelvey had written titled The Lost Rhymes at the Center of Everything Now Found Again.

“Each liturgy, no matter the depth of despair nor the elation of joy, possesses the intricately woven profession of Christian hope: that the good news of the Bible is a story that animates its readers and recipients with a newfound purpose because of God’s grace and mercy.

Participants were scattered among the audience. Recitations took place from every corner as their line was to be read.

“It ended up being really powerful,” McKelvey recalled. “It was like poetry in liturgical form.

“It was an oddly beautiful and powerful thing.”

Fast forward a bit. After struggling to make headway on a science fiction novel, McKelvey wrote his first liturgical prayer: A Prayer for Fiction Writers. It wasn’t an outlet for him so much as it helped to focus both his head and heart each time he sat in his chair each day to begin writing.

But it was beekeeping that really unlocked the potential of the project.

After sharing and suggesting the usage of the liturgy in an upcoming talk at Hutchmoot with Andrew Peterson, Andrew offered a wistful request.

“I wish I had a liturgy for beekeeping,” he said innocently.

This made sense, as Andrew is an avid beekeeper, but it set off something in McKelvey that brought all the pieces together in the tapestry of his vocational life. His calling had never wavered, but the expression was now taking a new light.

“At that point I thought, ‘Oh, yeah, this isn’t just a novelty piece for fiction writing,” McKelvey said. “This is an idea that could really serve the church.”

And serve the church it has, on bookshelves across the world, McKelvey’s Every Moment Holy has exceeded expectations in selling more than 50,000 copies, brought to life through an incredibly generous crowdfunding efforts from the entire Rabbit Room community that provided all costs needed for the book’s first printing.

“It wouldn’t have happened without that community,” McKelvey said.

Even now, a new liturgical project sits on the horizon: this one on the topic of dying and grieving. It will carry the same tenor as liturgies in Every Moment Holy, and McKelvey hopes the book—which he’s aiming to complete sometime in 2020—will serve the church in a topic that can often be taboo.

“Our process (in life) is learning to die to ourselves, that His life might be manifest in us,” McKelvey said. “That’s not just hyperbole; our actual dying is not an accident but something we’re moving towards as one more step in the process of surrendering ourselves to God.

“I hope that this can be a part of creating spaces within the body of Christ for these conversations to begin to happen.”

While taking on such a weighty topic, he hopes to continue pressing into the raw emotions of the content, crawling inside the pain of these circumstances to produce liturgies that reverberate with the hum of truth to those navigating times when truth and words can be hard to grasp.

‘Emissaries of a Coming Kingdom’

There is a common thread that bonds each of the liturgies in Every Moment Holy.

This exercise in thinking Christianly about various aspects of life is shrouded in hope. Each liturgy, no matter the depth of despair nor the elation of joy, possesses the intricately woven profession of Christian hope: that the good news of the Bible is a story that animates its readers and recipients with a newfound purpose because of God’s grace and mercy.

“One of my hopes is that it wouldn’t just be something that people would read, but that it would open up the possibility of writing those types of things themselves, offering in a contemporary voice what was common among Celtic Christians who had prayers for everything,” McKelvey said. “They had such a strong recognition of God’s presence in every moment: prayers for milking the cows, etc.

“They moved through their days with much more awareness than we tend to have.”

It’s this same hope that propels McKelvey, and us, into daily work. Through reading one of McKelvey’s liturgies or even writing your own for your work, we have an opportunity to grow in our own acute awareness of God’s presence in every moment, seeing more crisply the reality of co-laboring with God in the specific work of our hands he has called and equipped us to do.

This lies at the heart of Doug McKelvey when you compile all the puzzle pieces into frame. He writes, but he does so with intention. Specifically, to help the lives of the followers of God and participants in his church be shaped by rehearsing the new creation that is to come through their daily life and work—offering foretastes of the coming kingdom of God.

“The new creation is the restoration of what God made good,” McKelvey said. “That hope gives us the freedom and the gracious space to serve now the culture that we’re in, the cities we’re in now, and to offer a service where our hope is not dependent on the outcomes that we observe during our lifetimes.

“It opens the possibility of faithful stewardship of what we’re entrusted with, regardless of how it’s received.”

“We can rest in and trust that whatever the reality of eternity is, the redemption of those things that felt like futility but we faithfully did for God’s purposes, that the fulfillment and redemption of those things will be more magnificent than anything we could conceive of or imagine.

By serving others as a means of serving Christ, this view of future hope shaping present living fits lockstep with a Christian understanding of vocation.

Regardless of the degree, importance, or impact of the tasks and relationships we engage with on a daily basis, the gospel gives purpose that every good endeavor will find its full and right expression in the new heavens and earth. While we only may eek out a few notes vocationally through our time and life on earth, it will one day find its place in the grand song that, as Tim Keller says, we are all born remembering.

So work well with these truths in mind, McKelvey says. Maybe even grab your own copy of Every Moment Holy and find a liturgy that resonates. You can even create your own. But remember your labor and your liturgies are not in vain. For work, like worship, is formative, and is a means by which God is shaping us further into the image of Christ—our elder brother and true north.

“We can rest in and trust that whatever the reality of eternity is, the redemption of those things that felt like futility but we faithfully did for God’s purposes, that the fulfillment and redemption of those things will be more magnificent than anything we could conceive of or imagine,” McKelvey added. “It’s with that future hope in view, in the eternal city that is to come that is our home, that we’re liberated to live within the cities that we’re a part of now as emissaries of the coming kingdom and agents of its advancement.”

Gage Arnold is the communications director for the Center for Faith & Work Los Angeles and an MDiv student at Covenant Theological Seminary. He holds a BS in journalism and electronic media from the University of Tennessee.